CBS 58 Wall of Honor

CBS 58 is highlighting those who have dedicated their lives to serve our country. Members of the military and their families are invited to submit a photo of the military heroes in their life as a way of honoring their service to our country.

THANK YOU, HEROES!

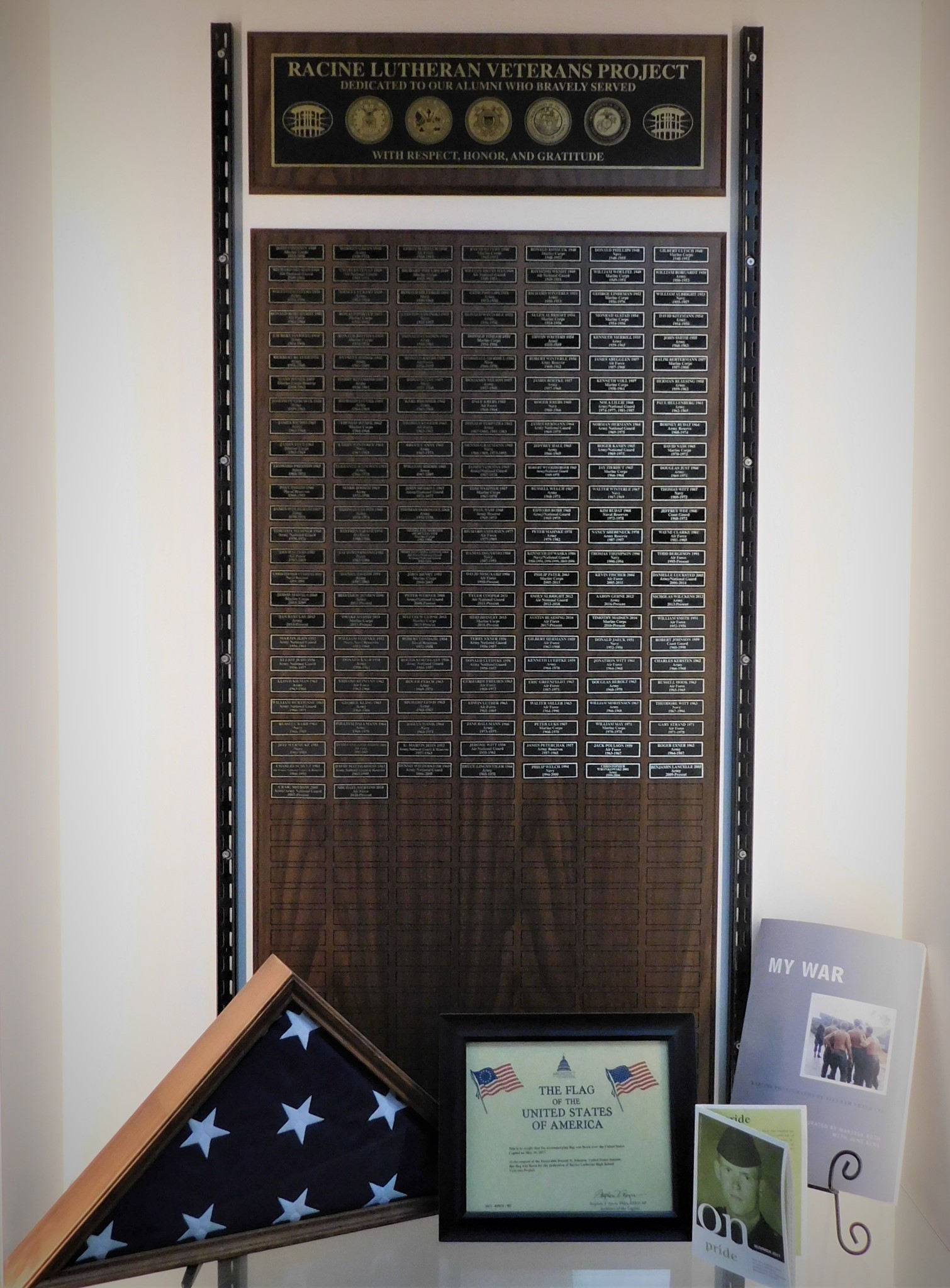

Several - RLHS Alumni 1944-2026

from Racine, WI

The Racine Lutheran High School Veterans Project honors alumni who have served in the Armed Forces. To date, 233 veterans' names have been added to the plaque that is beautifully displayed in the school's entryway. new names are added to the plaque annually on Veteran's Day.

Richard Corning

from Milwaukee

Joined the US Navy in August 1945 and served as part of the occupation of Japan after the war ended

Harold ( Babe ) Koeppen

from Milwaukee

My Uncle served on the heavy cruiser USS Wichita during WW II, His tours took hom from the North Sea escording conveys to Russia, battles in Mediterrean with Italian navy, finished in the Pacific supporting the island hopping battles and finally ended steaming to Japan after the nuclear bombs had ened the war

Robert Koeppen

from Milwaukee

My father served in 82nd Airbirne Gliders from 1942 to 1945. He served in North Africa, Italy, D-Day from France to Battle of the Bulge to meeting the Russians at the Elbe river. He took part in the 3 glider operations and helped liberate a concemtration camp.

John Koeppen

from Milwaukee

US Army Veteran from 1969 to 1971. i served in Vietnam with 9th Infantry & 25th Infantry Division as a combat Infantryman. In III Corp and took part in the Cambodian Incursion May 1970. On March 26 th I was lifted out oof the jungle on a mission and 3 days later I walking back home from combat. I was 19 when I entered the service and after 401 days of combat I was back home 20 years old.

Lauren K Glass

from Shorewood

I joined the Navy Nurse Corps in 1970 because of the need for nurses for Vietnam. Served on active duty at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. Served in the Reserves all over the USA. Retired as the Regional Nurse Corps Officer for the midwest

Christian Walters

from Elm Grove, Wi

Christian is a special operations aviation veteran, Apache and AH-6 pilot, and West Point graduate. After the Army, he became a husband and father and continues to serve causes greater than himself in business, his community, and Veterans via the Night Stalker Foundation.

Joel Walker

from Brownsville

Has served with honor and continues to serve veterans thru his membership and offices held in the Veterans of Foreign Wars for 52 years so far. He is also a Past State Commander of the Wisconsin Veterans of Foreign Wars

Julian Dziki

from Chicago

My father, Julian Dziki, fought in WWII as a United States Marine.

John Olson

from Glendale, WI

MSgt Olson served 22+ years of Service in the US Air Force and 17+ years as the Air Force JROTC Instructor at Greenfield High School. On 21 April 2026 he will have 40 years of Uniformed Service to this country. He has received numerous Awards & Decorations as a member of the US Air Force and under his leadership as an Air Force JROTC Instructor the program at Greenfield High School has received various National level recognition. He personally has been recognized 3 times as one of HQ AFJROTC Outstanding Instructors for his work with the Cadets.

Joshua Friday

from Oshkosh

Joshua joined the ARMY in 2005, 1 year after his step brother Daniel was KIA in Iraq. He became a combat medic in order to save lives on the battlefield. He is now at Ft Sam Houston, training NCO’s in the medical field, to lead. In July, 2026, he goes to El Paso to attend the Sergeantv Major’s Academy.

William A Backes

from Milwaukee (Bayside)

Vietnam Veteran 1971-72 Seabee RNMCB25 1970-1980 AFR 440th CES 1980-1990 Ret Msgt Legacy Life Member Veterans of Foreign Wars 1985 To Present VFW State Commander Dept of WI 2004-05

Kenneth Lindl

from Milwaukee, WI

from this article: https://www.milwaukeemag.com/profiles-in-courage-wisconsin-world-war-ii-veterans/ It is the most memorable pinochle game of Ken Lindl’s life. He was in the galley of his Martin PBM Mariner, a Pacific patrol airplane designed to double as a bomber and a small boat, complete with living quarters. They were based just north of Manila in the Philippines and patrolled the South China Sea. The summer of 1945 was relatively quiet for them. So quiet, in fact, that Lindl doesn’t recall ever seeing an enemy fighter nor facing fire from enemy troops or ships. He’d joined the Navy in 1944, before he’d graduated high school, intent on going to submarine school. They made him an aviation ordnanceman, and he manned his Mariner’s bow gun, positioned just ahead of and below the pilots, giving him sweeping views of every stretch of island and ocean they crossed. Two crews were assigned to each plane, and both crews were on this June 30 flight, putting more than 20 men on board. So during takeoff, Lindl was free for a four-man pinochle game. As the plane gained altitude, he noticed that the engine’s pitch didn’t sound normal. They didn’t know it at the time, but seawater was in their fuel tanks. “I looked out the porthole and could see the prop was feathering,” he says. He yelled for everyone to hit the deck, and they did, right before the plane crashed in a rice paddy. “We just saw a ball of flame come at us, and we exploded.” He was near an exit hatch and the first one out, moments before the co-pilot tumbled out on top of him. They scrambled away from the burning wreckage as ammunition from the Mariner’s five sets of .50-caliber guns cooked off. Other men scattered from the wreck. Four crew members never got out. Those who survived were too far from their seaplane tender, the USS Currituck, for immediate assistance, and they’d crashed a few miles from shore. Lindl, with but a small cut on his head, watched as medical supplies dropped from the sky, some from another Mariner in his squadron, some from a passing P-51 pilot, who’d attached it to a scarf. They gave what care they could to the injured, but one man was so badly burned and bloated that the only place Lindl could stick a morphine shot was his foot. Local natives trickled toward the crash. Lindl traded them his .38 revolver for some coconut oil, which they rubbed over the man’s charred flesh, and a wire bedspring to carry him. The natives led them on a 45-minute trek to a coastal village, through rice paddies and across a river so deep that water reached their armpits, forcing them to carry their comrade high over their heads. But even with more medical help at the village, the severely burned man would not survive, one of seven lives the crash claimed. Back on the Currituck, flown there by a Mariner that met them at the village, the survivors recuperated. Lindl’s head cut needed only four stitches, but he spent lots of time in sick bay, often playing cards with his wounded crewmates. Among them was his pilot, whose hands were badly burned. Rather than play his own hand, “I’d deal and play his cards for him,” Lindl says, and he’d wonder at being spared a worse fate.

Joseph F. LoCascio

My grandfather, Joseph F. LoCascio served in Incheon, South Korea and is a Korean War Veteran of the U.S. Army. My grandfather worked hard his entire life and believed a hard work ethic was the foundation for success. He was a wonderful man and our family is proud to call him a veteran.

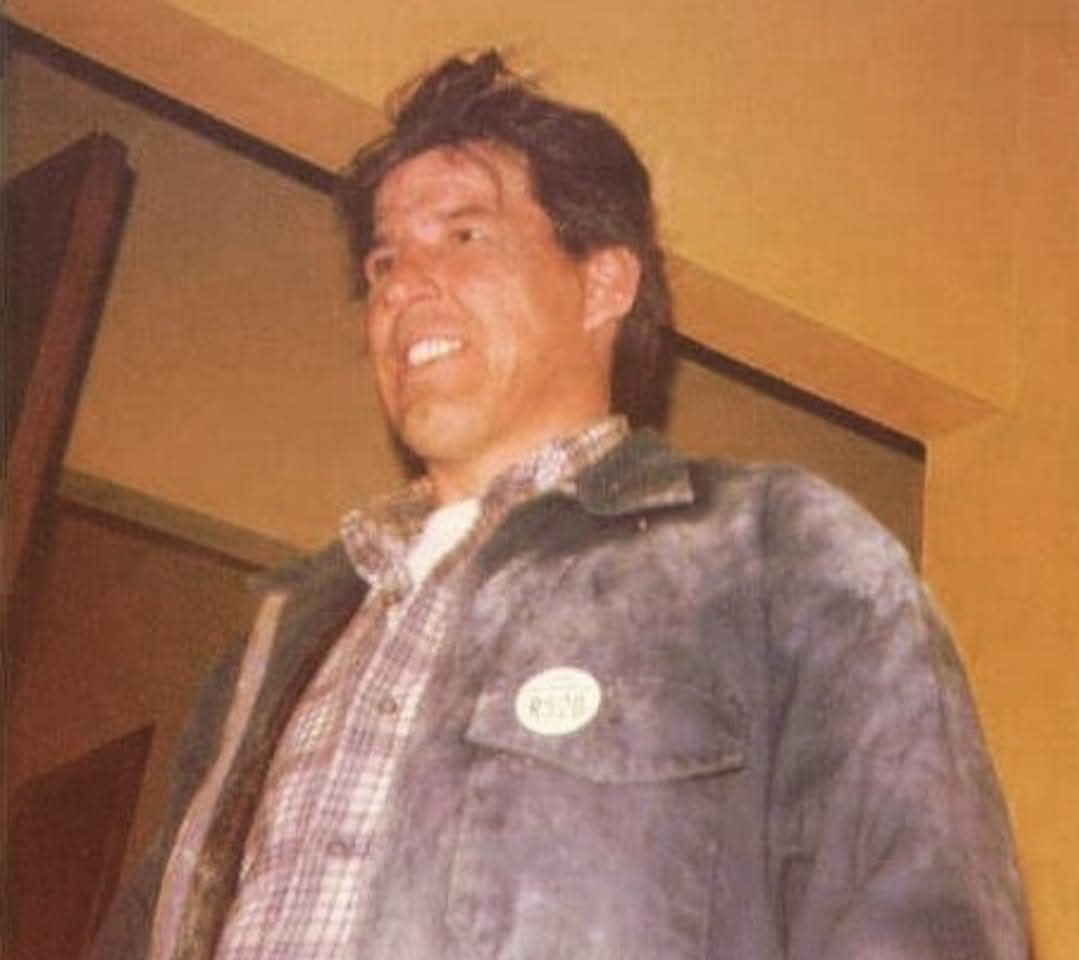

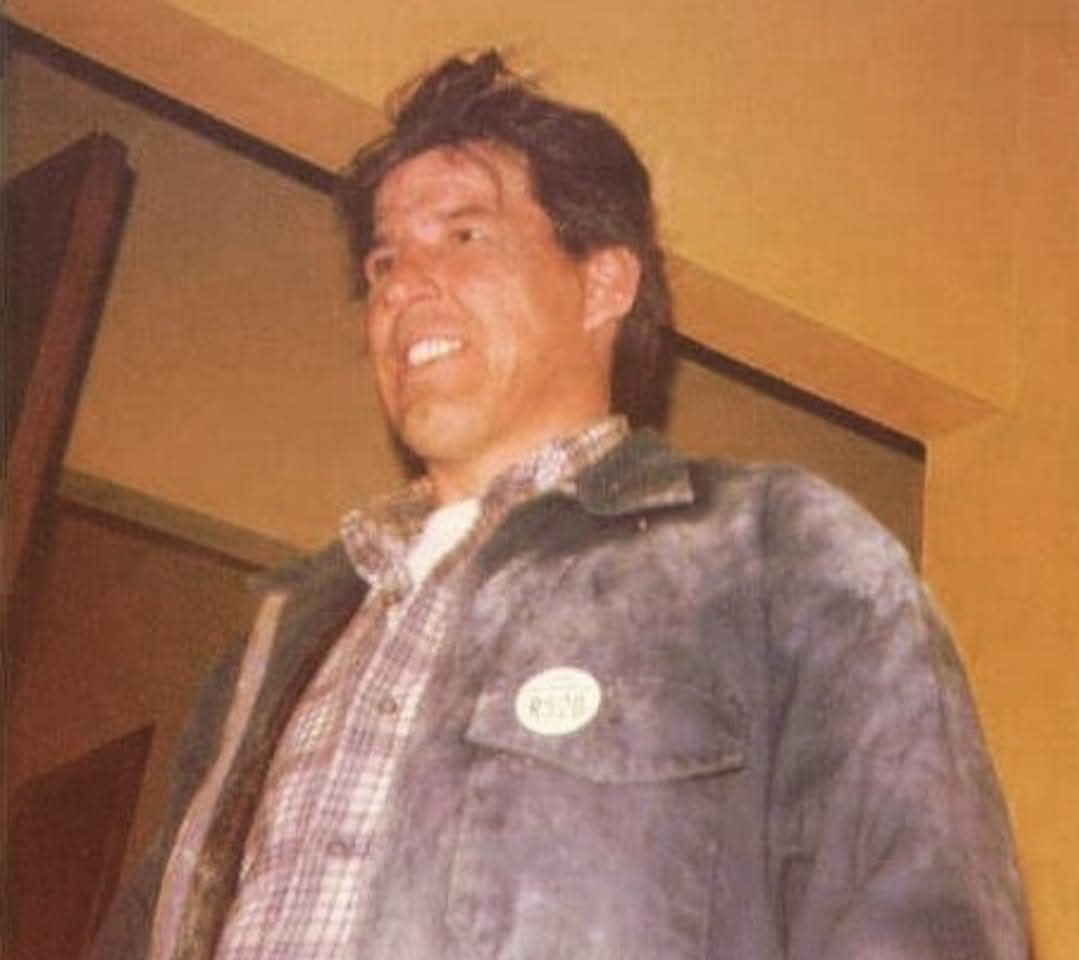

Tom Hull

from Milwaukee, WI

Tom was a hardworking and very family-oriented man who was also extremely proud of his Native American heritage and proud of his time as a paratrooper in Vietnam.

CBS 58 Weather Forecast